The Spires. Jan 2017

First night on the Spires trip, camping on the Pleiades.

I never set out for The Spires confidently expecting to reach the goal area, let alone the summit (despite our excellent leader). Too many things can go wrong in such unforgiving, wild country; too many others whom I deeply respect have failed one or more times to get there. Weather conditions, for a start, can wrest victory from your grasp, as the trek in is long and hard, and weather can make a huge difference when that is the case. But if you don’t set out, you haven’t a hope of succeeding, so our packs were on our backs, ready to give it a try, and if we didn’t get there, hey, we would have a fabulous experience in the wilderness anyway.

First night on the Spires trip, camping on the Pleiades.

Certainly, things didn’t begin in a way that engendered hope had I only been there to achieve summits. We had a few glitches on the first morning getting ourselves into position that set our programme back half a day, so we only made it to a saddle part way up the steep haul onto the Pleiades Range before we were obliged to end the day. Here there was camping to be had: well, there was fresh, running water the other side of the saddle, and the ground was kind of level. There was button grass everywhere, and bushes that did not respond at all to my request that they flatten themselves for my comfort. It was impossible to cook in such a bumpy, bushy vestibule, but the weather was mild, and we congregated on rocks to prepare our meals. The mood was jovial. Sunset that night was wonderful. I had an unexpectedly good night’s sleep.

Looking along the spine of the Pleiades.

Day 2.

The following morning, we set out to finish our climb up to the Pleiades Ridge. This is very, very steep country and the bush was thick, the going hard. Some members struggled, but thanks to a team effort, we all reached the ridge, and continued on our way along it, which seemed fine enough until we hit the final cliffy mound (huge) near the end before we would make a slight “left hand turn” at a different knob, continuing towards Conical Mountain (heading NNW, while the ridge leading to Pokana Peak deviated east). But first, as said, we needed to get around the final knob before the “intersection”.

Looking along the spine of the Pleiades.

We chose right. There was even a pad of sorts. It was so steep, I was grunting as I pulled myself up, and was accused of trying to have a tennis match. The last time I grunted like that was climbing up to Slatters Peak in early 2013. I’m not sure if it was the steepness (and extreme weight of my pack), or just the fact that my protracted illness of the last three months has robbed me of too much precious condition, but, whatever the cause, each major heave upwards elicited a noise worthy of Maria Sharapova (well, not quite that bad). This part of the route had a few spots where there was a very steep drop below our ledge. It’s funny how different varieties of exposure have altering reactions from people. Because there were trees below, and bushes to cling to, I felt fine, although, of course, I did feel the need to be cautious. Somehow the trees under me reduced any sense of great threat.

Looking down to the lake for night 2.

There is a small lake below the ridgeline after one has waved goodbye to Pokana Peak, and this was to be our campsite for the second night. As we descended to it, I noticed a lovely little beach with small sandy shore far below and hoped to camp there. Unfortunately, this spot was a bog, with a squelching, sinking vestibule area and button-grass lumps in abundance where my body should lie, but there was nowhere else to go by now, so I pitched and hoped it wouldn’t rain, which would turn my little depressed area into a tarn. I cooked on a nearby rock, joined by Johnny, whose tent was nearby. Our rocky kingdom was fine.

Rohan and David survey lakes two and three, beyond our own one, on Day 3

Day 3.

At last, after three days’ steady, and fairly exhausting climbing and pulling and heaving and high-stepping, we were heading for our first actual mountain (still laden with our heavy packs), and, joy of joys, it was an Abel: Conical Mountain. It still looked like a giant ahead as we snailed our way towards it. I was very happy to at last have a summit under my belt, and an Abel at that, but the big one lay ahead.

Me, above Lake Curly, looking towards Mt Curly.

Shining Mountain is lower than Conical. That should give heart, but the drop between the two did not. There was more height to gain, and more bush to fight for my out-of-condition body. We celebrated the views from Shining fairly early in the afternoon. The day was now very hot, and progress was like a pyrrhic victory in a battle.

Dale on a fun spot beyond the summit of Conical Mountain.

Shortly after summitting this one, our noble leader pointed out that descent into the valley way, way below (almost out of sight, the land was so steep), would be a hot and unpleasant affair on such a day. He said it would be possible to camp up there and still climb The Spires on the morrow.

Shining Mountain shelf campspot. The Spires lie ahead there across the valley.

Now, considering the fact that I was of the opinion that if God wanted to choose an earthly spot for heaven, He could hardly go better than the one in which we were then seated, this was joy to my ears. The view was fabulous; we were high in the sky with a sense of infinite space all around and mountainous views to die for. Yes, yes, please: I wanted to sleep just here, to linger in this place and soak it all in. THIS is why I bushwalk. This is the reason I come, and I did not want to go away. We stayed.

I chose a secluded spot beyond the other tents and enjoyed scenery that filled me with joy and peace. My spirit soared with pleasure. This is The Sublime, not just the beautiful. Spiritual pleasure in such a place is not confined to indigenous people. Wilderness is important to the soul of all of us: the chance to be in a place of the infinite and be still in a way that cities do not allow. My church is up here, not in a dark, musty building made by humans.

I wandered about, chatting, but mostly I sat and stared, just enjoying the existential pleasure of being. I no longer cared whether I made any more summits. I felt complete.

Day 4.

After a glorious start to the day, the climb down to Reverend Creek and then up to The Font was bothersome, done in temperatures that told you swimming would be a much more pleasant pastime than this. However, we were there to climb, not swim (that would come later for the Brave).

We dumped our packs at The Font, and began the serious business of our actual mission: to climb The Spires. But first, the vote was to climb Flame Peak on the way, to score two easy points in case we couldn’t get the Big One, which was much harder.

Unbelievably, my camera let me down at this part of the day, and refused to allow me to shoot. The others suggested that the heat was the problem, and they were right: it functioned again that night, but for these two peaks, the object of my quest, I was effectively cameraless.

But let me describe the route up The Spires. From the Flame-Spires saddle, we descended around the face of The Spires, curling right, until we found a ledge that led to an internal saddle within the Spires summit. The going in this part was easy, with plenty of bushes to grab. It was even shady. Hoorah. It was fabulous to be free of our packs at last. I felt so light and agile.

And now the photos move straight to sunset, due to the broken camera.

After the internal saddle, the fun of the final climb began. We curled left, to be faced with a sloping rock that had no handholds for safety. We had been warned. Some crawled; some wormed. We all got there. It didn’t last long. First object overcome. Had anyone fallen, it would probably have been fatal, as the drop, although not of Feder proportions by any means, was probably enough to be one’s final acrobatic act.

After the slope, the rest was fun. Yes, the drop was now monstrous, but the handholds were secure, and I just didn’t look at the drop, so can’t tell you anything about it, although I could feel Great Space below. With security of holds, it didn’t matter. Eleven set out for the final climb. Eleven made the summit. Fantastic job, oh leader (who, having been there before, and now sporting some gastric bug, did not accompany us).

It was time for another vote. Should we go back the way we came and face the slopey bit again, or do a circuit continuing on towards False Dome, maybe climb it too, and come back that way? We voted for a circuit, so off we set. The saddle before the first internal mound offered no way down. Nor the second. After much climbing and humming, we voted to reclimb The Spires from this new direction, and retrace our steps. It was a fun adventure, and a good way to fill the afternoon. Soon enough, we were at the campsite above The Font, choosing our real estate for the next two nights and enjoying the views this place had to offer (tremendous).

Day 5.

This was to be a packless day, climbing Innes High Rocky, a mountain that pleased me greatly because of its stunningly remote position. Dale – one of our more adventurous members, and an amazing team member who averted many an attempt at team failure with his admirable ability (and astonishing willingness) to carry other people’s packs when they were struggling – went even more remote than that, and climbed Philps Lookout as well. The rest of us found Innes High Rocky to be exhausting enough on a day that felt well over thirty, and in terrain that offered very little water, but button grass higher than my waist to overcome for huge stretches.

One of my chief memories of this day is of us all crouching beside walls of rock, trying to shelter in tiny patches of shade. I even voluntarily sat on a scoparia bush, as that was the only way I could get some shade. This is not a hobby I will pursue. The day was ten hours long, even though the actual climb only took five and a half hours. The breaks were needed!! I enjoyed the chance to linger longer in a place that I will probably never go to again.

Innes High Rocky still a way off yet.

Day 6.

The Font

Now we entered the business end of the trip. Camped up high, we had access to BoM readings, and the weather for Tuesday was pretty bad; for Wednesday, absolutely deplorable. We had two days to get out to beat this change. If we could reach the Lake Gordon shore by late Monday afternoon, there was a chance Andrew could get us all out in his flimsy (sorry Andrew) dingy before the projected winds made the lake perilously rough. It was now Sunday morning.

Off we set, on a mission, and successfully walked two days at once, in what was a long day. This day was so windy, I had insurmountable trouble walking in anything resembling a straight line, being constantly thrown to the side by sudden gusts. I found it exhausting fighting the wind like that all day. We camped this night at the lake of our second night.

Day 7.

On we pushed in our race against the weather, but not so fast that we had to omit Pokana Peak, the final mountain, and Abel, of our quest. It was grand to be once more, albeit it only momentarily, free of our packs.

Pokana summit view

The day was long, the work was dehydrating, with the yabby holes from which we’d drunk on our way in now almost fully dried up by the way out. Valiantly the group pressed on, well aware of the penalty of easing off.

Andrew’s first trip across the Lake was dicey, and he feared it would be his last for the day, leaving a herculean task for the morrow, but he realised he could make another, and yet another, so did. My tent was already up when the boat returned, but I was neither worried nor disappointed – although I did brace myself during the night for a possible long haul at this spot. I knew that on the Wednesday, if still stranded, I would not be able to cook in the winds that had been forecasted, so prepared mentally for no warm meals as well. Meanwhile, the lakeside spot was rather fun, and I cooked a huge dinner in celebration that I didn’t need to eat abstemiously any longer (Laksa soup, “roast chicken” – so they say – plus apple pie for two for dessert). I had enough food still to last most emergencies, unless they endured for about a week. My rucksack still had over 2 kgs of extra food (I suffer from food angst, so had taken a little too much to cover for this), plus I had left a stash at the lakeshore in case.

Next morning, most unexpectedly, we heard a boat at 6 a.m., and saw Andrew, somewhat hassled by the emergency of the situation and the task of getting two more boatloads out before things became impossible. Under deep stress, knowing what he knows about boats and lakes and winds, he expertly handled this final exit. I have to confess to being terrified as we roared our way through closely placed dead trees in the lake at frightening speed (sorry for the lack of trust, Andrew, but I am not used to doing this). My only consolation was that I believed Andrew wanted to remain in life himself, so would not take unreasonable risks. He knew what he was doing. We were out. Twelve had set out, twelve arrived safely and successfully home. What a fabulous trip that will last in our memories for as long as we live. After everything was packed up, we drove eagerly to the Possum Shed to celebrate our expedition with Real Food.

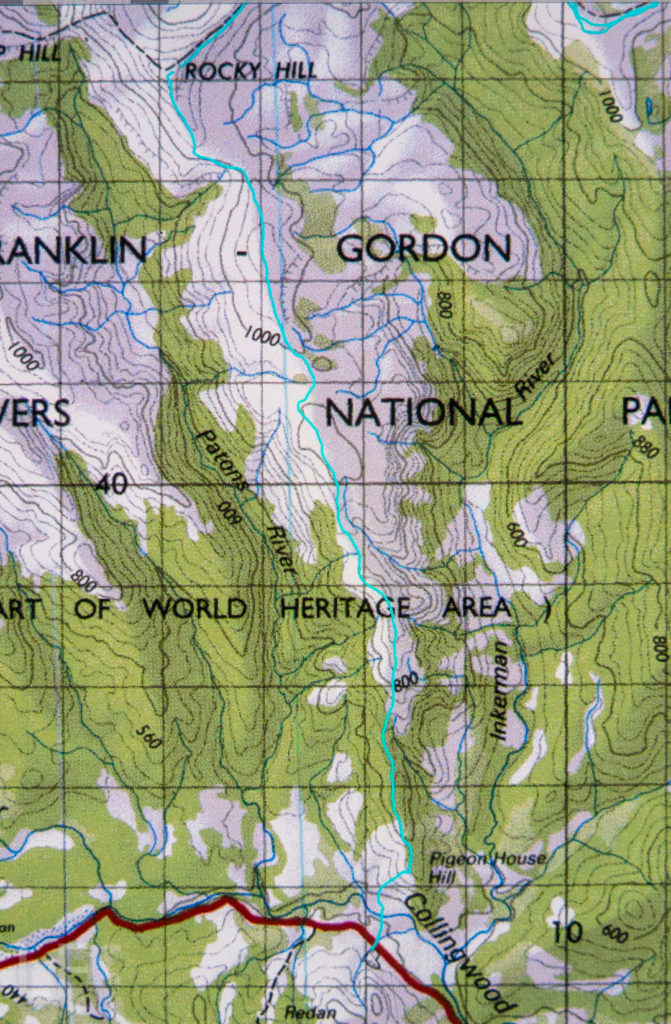

Please note: this is in a category listed as “Distance Trail”. It is there because it covers 8-10 days’ worth of distance. Note, however, that there is NO TRAIL. This is pure wilderness, and needs expert map reading and much more to be undertaken.

It was so worth the day’s effort to see what we were now seeing: viz, a vast array of magnificent mountain friends, almost all of which we’d climbed, although not all of which we could readily name from that angle. In particular, we adored the different perspective on Eldon Crag and Peak; it was also amazing to see the seemingly ubiquitous Frenchmans Cap, which must be the “most seen” mountain in Tasmania. Way to the north east, we could see as far as Cradle, Barn Bluff and Emmett, as well as Pelion West, Ossa, Thetis, Manfred, Cuvier, Byron, Geryon, Acropolis and Olympus – in fact, the bulk of the mountains that line the famous Overland Track. This was not a view that you just noticed and then departed from. You had to stay for a long time. We bounced around with delight, and stayed all night. Well, in fact, we stayed two nights, so good was the view. The fact that we’d arrived up there by 3 pm meant we certainly had time to progress further along the ridge as far as Mediation Hill, but we were in love with this spot, and we stayed put. We thought we could make it to Pyramid Mountain (our next day’s objective) and back from there, although it was a slight gamble given the short days at this time of year.

It was so worth the day’s effort to see what we were now seeing: viz, a vast array of magnificent mountain friends, almost all of which we’d climbed, although not all of which we could readily name from that angle. In particular, we adored the different perspective on Eldon Crag and Peak; it was also amazing to see the seemingly ubiquitous Frenchmans Cap, which must be the “most seen” mountain in Tasmania. Way to the north east, we could see as far as Cradle, Barn Bluff and Emmett, as well as Pelion West, Ossa, Thetis, Manfred, Cuvier, Byron, Geryon, Acropolis and Olympus – in fact, the bulk of the mountains that line the famous Overland Track. This was not a view that you just noticed and then departed from. You had to stay for a long time. We bounced around with delight, and stayed all night. Well, in fact, we stayed two nights, so good was the view. The fact that we’d arrived up there by 3 pm meant we certainly had time to progress further along the ridge as far as Mediation Hill, but we were in love with this spot, and we stayed put. We thought we could make it to Pyramid Mountain (our next day’s objective) and back from there, although it was a slight gamble given the short days at this time of year.