I am also, however, a task-oriented person, who likes to achieve the goal for the day. After two failed attempts at the summit of Byron in as many tries on club walks, it was time to be my own boss. I wanted success this time. I’d look up how many points I got some time or other. The summit was my goal.

First official day of autumn. Frost says “Good”.

First official day of autumn. Frost says “Good”.

The trip to the ferry “threatened” to be the highlight of the day. Sunrise was magnificent as I drove up the Poatina Rd to the central highland; on top, autumn announced its arrival with glorious patches of sparkling frost. Lake St Clair (Leeawuleena – magnificent name) was shrouded in mist. It was going to be a gorgeous day. A temporary dampener, however, was put on matters when Steve, the cheery, affable ferry driver, informed me that he was finishing up at the end of the week. I wonder if his employers understand what an amazing asset they’re losing. Steve’s friendly and knowledgeable trips have come to be a grand entree to every expedition in the area, aiding in the excitement of each venture.

You don’t replace someone like that easily: a new ferry driver, sure, but an asset like Steve … ever?

Leeawuleena (Lake St Clair).

Leeawuleena (Lake St Clair).

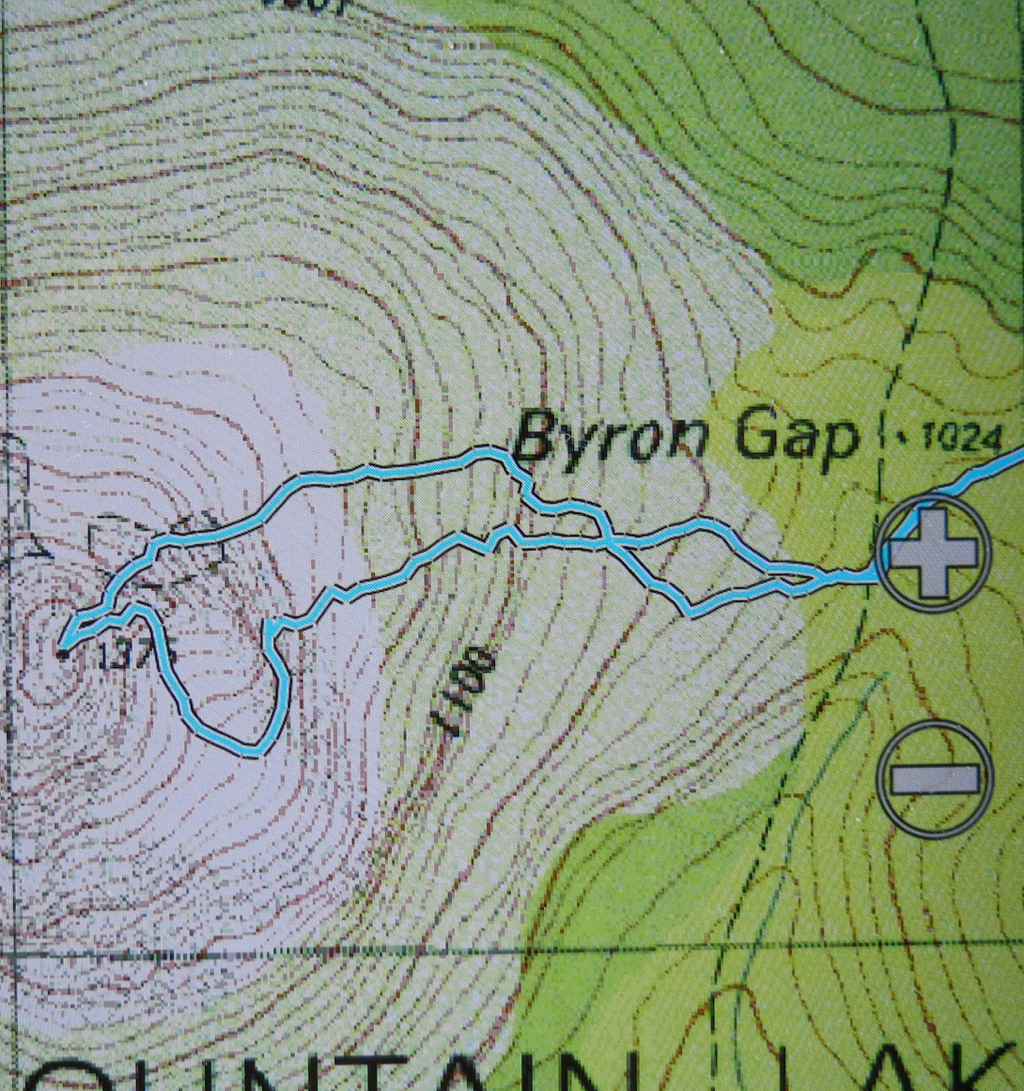

I love the forest lining Leeawuleena – always so rich, lush and vivid in its greenness. Happily I strode out, staring intermittently up at my mountain, and at all the old friends that surrounded my journey. Unfortunately the atmospheric mist had already evaporated. It took 17 mins to the turn off; and 59 more up to the top of the Byron gap, where the real work would begin. This is the third time I have walked this “track”, yet I managed to dream my way off it twice on this trip. Fortunately, the first time was right near the start, so I turned on my gps tracker in case I should need it on the way back down. The black dashed line for track on the map bore no resemblance whatsoever to the track I was marking. I was glad that I wasn’t trying to navigate myself to the line on the map for safety.

Paths like this require constant attention to stay on them.

Paths like this require constant attention to stay on them.

After the gap, I had to make my own way to the top. There was talk of a cairned route if you happened upon it. I didn’t, so nosed my way to my left through pretty thick scrub and along a rather precipitous cliff-ledge until I came to a promising looking gully leading upwards. Happily, my map indicated that this could be followed to the final summit mound (which would hopefully not be fortified by more unmapped cliffs. One never knows on maps that don’t back up photogrammetry with cartography). The map certainly didn’t tell me that the rocks comprising this backdoor entrance were wash-machine size, with some heaving needed sometimes to get to the next layer. I began to worry about the return journey and the still existing possibility of getting trapped with no retreat reasonable. I hankered after a nice easy cairned route. I sensed the effects of adrenalin.

Byron’s pandani forests are a delight

Byron’s pandani forests are a delight

The mound ahead looked as if it could contain the summit, but I didn’t dare invest too much hope in this. Too often such mounds lead to a view of the next, higher one. This one, however, offered my approaching form a sighting of three little rocks perched atop one another. I had made it.

Looking at Manfred, Horizontal Hill, Guardians, Gould, Geryon et al

Looking at Manfred, Horizontal Hill, Guardians, Gould, Geryon et al

I actually felt nauseous with anxiety, as the descent still lay before me. I didn’t linger on top like I normally do, just in case I needed lots of time to find a way down. Besides, lunchtime hadn’t quite arrived yet. I took photos and then set out to try my luck on the return journey. This time was different. I happened on a cairn on my chosen early section, and one cairn led to another. Eureka. This route was SO easy. It was 30 mins faster than my way up – most unusual for me. I usually ascend faster than I drop, due to my eagerness to see the top and my hatred of stopping before I’m there. I am not normally happy to leave, so dawdle a bit.

View to Horizontal Hill, Guardians, Gould, Geryon and more

View to Horizontal Hill, Guardians, Gould, Geryon and more

In the safety of the saddle, all work behind me, I enjoyed my lunch, looking out at Frenchmans Cap. I was easily in time for the afternoon ferry, except that it had been cancelled. I was the only customer. Now began the long walk home. No matter. The forest is wonderful. I slotted into my rhythm, walking and singing my way through fairyland back to the visitor centre, where I enjoyed a delicious veggie curry before embarking on the drive home in the fading light, shooing countless conferences of wallabies, all sitting erect in the middle of the road chatting, unwilling to have their colloquies interrupted by a mere vehicle. I stopped to let each group finish its important discussion. My speed ranged from 0 to 50 km.p.h in deference to their need to converse on dirt road.

An unusual perspective on Olympus, with Leeawuleena and Lale Petrarch balanced on its outstretched arms.

An unusual perspective on Olympus, with Leeawuleena and Lale Petrarch balanced on its outstretched arms.

The challenges of the day, apart from driving, climbing, and avoiding garrulous marsupials, involved walking 36.5 “kilometre equivalents” (where 100 ms climbed = 1 km equiv). Quite an active day.

The more southerly route is me fumbling my way to the top, edging around cliffs. The northern one is the cairned route. which I happened upon up the top.

The more southerly route is me fumbling my way to the top, edging around cliffs. The northern one is the cairned route. which I happened upon up the top.