Nescient Peak. There was something incredibly tranquil about this day – perhaps partly caused by the fact that this was the first day since winter that there was a feel of summer in the air. The Examiner reported today “Summer is here”, and indeed it had arrived. Perhaps the feeling also sprang from the fact that this was a Monday, and one doesn’t normally climb a mountain on a Monday, but my friend Angela had the day off and I was free, so here we were in good spirits, ready to try the taste of another mountain on Tassie’s wondrous smorgasbord of high points.

I have decided I love climbing mountains that have received bad reports elsewhere. It’s not that I’m perverse, seeking to find pleasure where others have found pain: I think it’s just that if my expectations are set low, then reality has a good chance of bettering my anticipations, and I am left pleasantly surprised.

The writer of the Abels essay on Nescient Peak was quite clearly disenchanted: in the opening sentence of instructions on how to get there, the reader is admonished to wear scrub gloves and gaiters, as if this were the most important thing one would need to know about this mountain. I suggest the author visit the Coronets to gain a different perspective. It made us feel as if this mountain were a kind of medicine that good people had to take in order to keep healthy. As a result of the warnings, we kept commenting to each other on how easy this bush was to get through; how light and malleable the small branches.

We did have to agree that the first glimpse of our mountain was “unremarkable”, but I still found it attractive enough to want a shot from a few angles. The book insulted it by only publishing an image of the very prickly Coprosma nitida (mountain currant), as if any image of the peak would detract from the beauty of the book – like dismissing an atonal person from the choir.

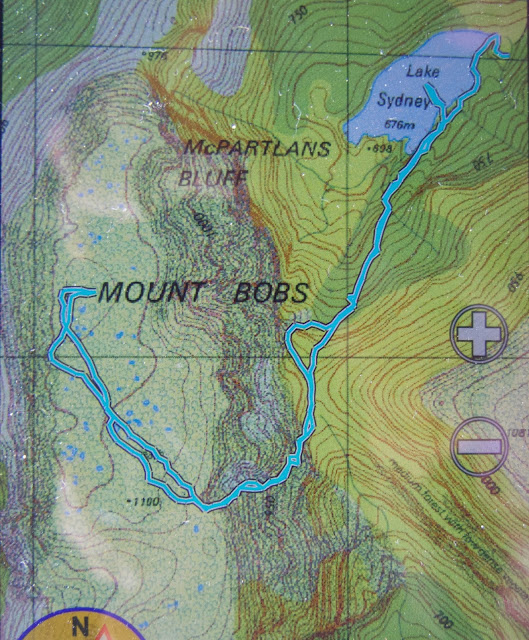

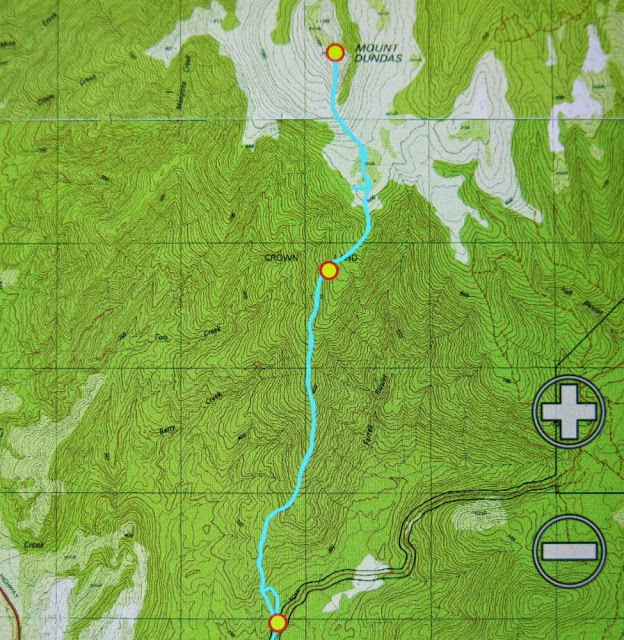

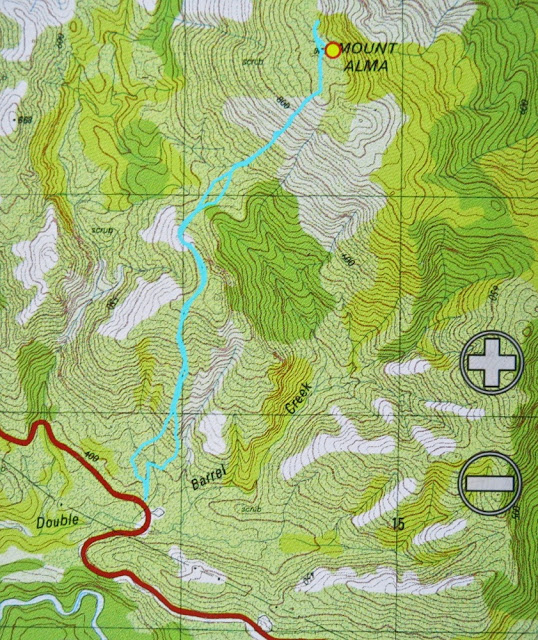

Next criticisms were directed at the apparently awkward navigation (in nuce, head west, over two contour bumps and the third and highest of the contour collections is your goal), and the fact that apparently the ground was very rough underfoot. We were in the bush. The ground was neither better nor worse than any other bush. If you want a smooth highway, visit QLD. They vacuum the forest floor there at 7 a.m. in case tourists should sue them for having uneven ground (I kid you not. Pity about the hideous noise and smell of petrol in a National Park). Again, expecting the worst, we felt nothing but pleasure in not finding it. You could run through that bush (if you were an orienteer), and the rocky knolls were fascinating and shapely. I loved them, and climbed over them on purpose. “This is fun”, we agreed to each other as we climbed.

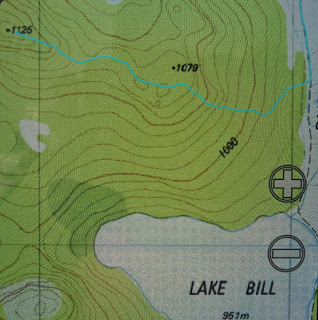

The “difficult to discern” summit stood out loud and clear to us, and even the complaint about the presence of trees fell on deaf ears. We enjoyed having a patch of shade in which to enjoy the view and have our compulsory summit-lunch, and I liked having a frame for the scene provided by leaves and trunks. I don’t want that on every mountain, but was happy to have it on this one. It seemed appropriate here. Of course we could see Mt Rogoona, but what that interested us the most was the unmentioned (by the book) King Davids Peak and Solomons Throne: it was fun to see these old friends from a different angle. Lakes Bill and Rowallan were very appealing from up there. And on the way down, once you’d started the very steep descent from the high moorland, we enjoyed views of Lake Rowallan that did not disappear, and that got bigger with each step. We’d taken, in walking time, 2 hrs 15 up; 2 hrs down, which made it a great daywalk, and meant it was short enough to have what was, for us, an uncharacteristically late start. Perhaps that also helped create the feeling of tranquility that I referred to in my opening sentence.

Confessions of a sinner, in case it helps: that ‘up time’ includes mislaying the track somehow: one minute we were on it, chatting away as we climbed, the next we weren’t. I am always a person on a mission on the way up anything, and Angela is a very agreeable soul, so I suggested we just bushbash our way south until we happen to intersect with the pad, and she agreed that would be fine. I’d much prefer that to wasting time finding a pad that you don’t really need anyway. As predicted, we did get back on to it a bit later.